A prose response to Philip Cashian's String Quartet No. 1, this post originally appeared as part of 'Did I Hear That?,' a creative collaboration with the Royal Philharmonic Society.

He moves on, descending past the flat where the seamstresses work, plucking stray threads from their cloth; past the dancers lined up at their bar. He wishes he could watch and linger to absorb their grace, but he knows that is impossible. Water drips from a concrete beam, skips the neck of a green glass bottle and puddles on the floor.

‘Here, it’s the adder’s servant!’ said another.

‘Pssssstttt, hisssssssssssssss.’

‘Get him, get him, get him!’ they chanted.

He cannot recall a single daylight outing since that has not been soured by hisses.

Anis almost gave up, but then the fathers began to take their turn, attaching rocks to each end of a rope and flinging it at his ankles as he passed. They dragged him to the ground, then set him free again. Afterwards, they allowed their sons their sport – chasing Anis with hooked poles, made sticky with birdlime. There was nothing he could do but press on with his escape, watch as hatred sunk its roots and flourished all around him, firm as weeds in stones.

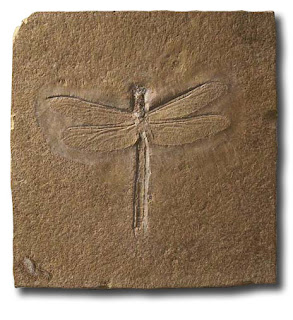

ANISOPTERA'S ESCAPE

The plains are black tonight beyond the edge of town.

Sitting on the flat roof of the tower block, Anis watches the last embers of

the cloud bars fade and day rolls over the horizon. He unfolds his legs and

rises to his haunches, gibbous as the waxing moon.

Anis likes spending his days up here, observing the scything

gulls and crows, the aircraft taking off and landing. The glistening of the reservoir.

It is the only place where he can feel unsullied peace and joy. He looks over

the edge and, sixteen floors down, a man backed against the railings by a streetlamp

bends steel wire into insect shapes for children. A cue: Anis gets to

his feet, checks the clasps on his dungarees and picks up a battered leather

holdall. It is time now for his walk.

First he must negotiate the stairwell, the walkways,

the recesses, slipping by unnoticed. He is not good at this - a man of such

ungainly bulk is prone to being seen. Before he’s taken three steps down he’s barged

to the wall by a young man hurtling to the roof before the fire-door swings to

again. Perhaps he hadn't t seen him. Perhaps the young man was rushing up to shout a

warning: ‘Anis – look out, he’s on his way!’

Anis waits, presses his back into the wall and

breathes in time with the warm air gusting through a vent in the bricks. Steam

as a bathroom window creaks ajar. A girl twangs on the floss she’s pulling

through her teeth.

He moves on, descending past the flat where the seamstresses work, plucking stray threads from their cloth; past the dancers lined up at their bar. He wishes he could watch and linger to absorb their grace, but he knows that is impossible. Water drips from a concrete beam, skips the neck of a green glass bottle and puddles on the floor.

Out in the street, Anis hurries from the estate, cocooned

in his coat and careful to keep close to the buildings. Paving soon gives way

to open ground and he can push his shoulders back and lift his face up to the

night. The walk is not a long one, but he appreciates each pace of it: the scented

drifts of mayflower, the scuttling life among the hedgerows, spits of evening

rain upon his brow.

Anis’ preference is for freedom, not enforced

seclusion – he has tried so many methods of escape. Once, he crossed the metal

bridge above the ring-road, stood among the shattered hub caps and the dirty

piles of snow with thumb outstretched. He waited there all day, until the light

vanished into the grey of the verge and he could be seen no more. Not a single

person stopped, slowed down, or even beeped their horn.

Then there was the time he rowed a boat down the

canal. He made the coracle himself, bending willow for the laths of the hull and

hazel-wood for the weave. He even learnt to steer the craft in clear, straight

lines. But soon he ran aground on a dam of soft drink cans, a traffic cone and

matted clumps of straw blown from the park-keeper’s cuttings.

Undeterred, he had no choice but to make a bid for

airborne liberty.

Anis reaches the door of the lock-up, takes out his

key and rolls up the shuttered entrance, taking in a draught of grit and

grease. He puts his holdall on the table and flicks the light-switch on.

Overhead, brightly coloured stalactites hang from the curve of the roof. Anis

takes down a blue china cup from the dresser and fixes himself some tea before

setting to work on the finishing touches to his project. It has been a very

long day.

Tomorrow has been chosen for the launch of his

escape. Long before the local residents start shovelling cornflakes into their

mouths or spreading marmalade on toast, Anis will be gone from here.

His desire – no, his need – to flee had started with the hissing. Twins in matching

sundresses swinging from the railings: they faced outwards, arms locked behind

them, heels braced on the low wall. Convex grotesques.

‘Pssssstttt, hisssssssssssssss,’ said one.

‘Here, it’s the adder’s servant!’ said another.

‘Pssssstttt, hisssssssssssssss.’

‘Get him, get him, get him!’ they chanted.

He cannot recall a single daylight outing since that has not been soured by hisses.

His favourite part to work on is the cockpit – more

properly, the thorax - weaving bright cavities that house the heart and hold

the legs and wings together. It is delicate work, but Anis possesses a

dexterity and patience that is startling. He has built a loom in the lock-up,

strung with a sturdy warp and wefted with fine threads. The silks he has chosen

are jewel coloured: emerald, garnet, sapphire, roseate pearl. Dazzling patterns

emerge as he works the treadles in the quiet of the night and likes to imagine

how life would be if things were different, can almost think about this place

as home. Almost.

But then the mothers with their wagging fists and

tongues flock back into his mind. They have accused him of poking and snatching

the eyes of their daughters, of sewing their mouths and noses shut while they slept.

It was even said he’d weigh your soul and sell it on for scrap. He never

understood their gibes and leers, why they chose him as the object of their

bile. He guessed the twins’ taunts had got so out of hand they’d turned a

rumour into fact. And he accepted people looked at him and didn’t feel surprise,

with his bulbous, florid nose, his giant’s span. But Anis had no courage to fight back or to ask questions, and let himself be bullied into

silence.

It is true that Anis didn’t always know success.

There have been many failures in the way of his creations: legs that got up and

walked off by themselves, eyes that shrank and failed at the light, wings that folded

when they were meant to propel. His attempts to revise the blueprints were

protracted, agonised over by the glare of a head-torch. Again and again he ran his

diagnostics on the lift and drag, assessed dynamic pressure, accelerated all

six degrees of freedom, but always test flights turned to wreckage, time trials

stuttered to a halt. He looked to birds in flight for the answers to his

problems, queried the fall of sycamore seeds for clues.

Anis almost gave up, but then the fathers began to take their turn, attaching rocks to each end of a rope and flinging it at his ankles as he passed. They dragged him to the ground, then set him free again. Afterwards, they allowed their sons their sport – chasing Anis with hooked poles, made sticky with birdlime. There was nothing he could do but press on with his escape, watch as hatred sunk its roots and flourished all around him, firm as weeds in stones.

‘Pssssstttt, hisssssssssssssss.’

At last, one Tuesday afternoon, Anis found hope circling

unaided in the skylight and saw that it was possible: the gold flashes of the wings, the majesty of flight.

Success! Even with his heft, he felt the lightness of his designs and flung the

shutters wide in celebration.

Then, a pass of grief as he watched them go their

own way, darning air above the children on the path, who turned and squealed

with glee. Would that they weren’t blind to the humanity of their maker, to his

gifts, to his capacity for wonder.

But they were. They are. And he must leave.

Tonight’s no time for sentiment.

He has replicated his best prototype and now readies

the new fleet, one last frantic assembly of legs, wings, antennae, bodies,

heads. Fixing, adjusting, finishing.

When he is done he surveys the work, grabs up the battered

holdall and packs his dragonflies in careful, tissued layers.

Sunrise and Anis sets off for the roof. He can

afford to be less cautious in the mornings, deserted and still as the benches

and the courtyards are at this time of day. He makes his way back up the

stairwell, pushes through the fire-door and sets his bag down gently on the

ground.

One by one, Anis plucks the hairs from his own head

and lays them out. When he is ready he unclasps the holdall, reaches in and

takes out a single dragonfly. He takes a hair, wraps it round, fastens it like

a rein, then repeats the action until a thousand Skimmers, Hawkers, Chasers,

Darters, Thorntails and Dropwings are harnessed, ready to take flight.

Anis takes a needless run-up to the edge and notices

the distance is unusually clear today. Still no sign of any souls below, just the electric thrum of a milk-float on its rounds.

His final checks complete, Anis does not waste a

single minute more. Eagerly he flicks the reins, watches his fleet rise and

takes one final leap of faith.

No comments:

Post a Comment